Optimizing Performance: Nutrition Strategies for a Soccer Game

- By Amy Stephens RDN CSSD

Soccer is an endurance sport that requires a steady supply of nutrients. Optimizing energy levels and performance involves special attention to fueling strategies before, during and after training and competing. In order to keep up with high energy and fluid requirements, special attention needs to focus on practices, games and tournaments. Stay ahead of your fueling by following these guidelines.

Pre-Game Nutrition (1-4 hours before the game):

Hydration: Start hydrating well in advance. Aim to drink water consistently throughout the day leading up to the game. Avoid excessive sugary drinks and caffeinated beverages.

3-4 hours before kick-off:

Meal: Consume a meal rich in carbohydrates about 3-4 hours before the game. This could include pasta, rice, bread, or potatoes. Carbohydrates are crucial for providing the energy needed during prolonged physical activity. Include a moderate amount of lean protein (e.g., chicken, fish, tofu, or peanut butter) in your pre-game meal to support muscle repair and maintenance. Keep fats moderate in your pre-game meal to avoid stomach discomfort. Opt for healthy fats like those found in nuts, seeds, or avocado.

1-2 hours before kick-off:

Snack (Optional): If your pre-game meal is more than 4 hours before the game, consider a small snack. A banana, pretzels, peanut butter on crackers, yogurt, or a granola bar can provide a quick energy boost.

Avoid Heavy or New Foods: Stick to foods you are familiar with and avoid heavy, greasy, or spicy meals that may cause digestive issues.

Photo credit Claudia Heitler

Hydration During the Game:

Water: Drink water regularly throughout the game. Small, frequent sips are better than drinking large amounts at once.

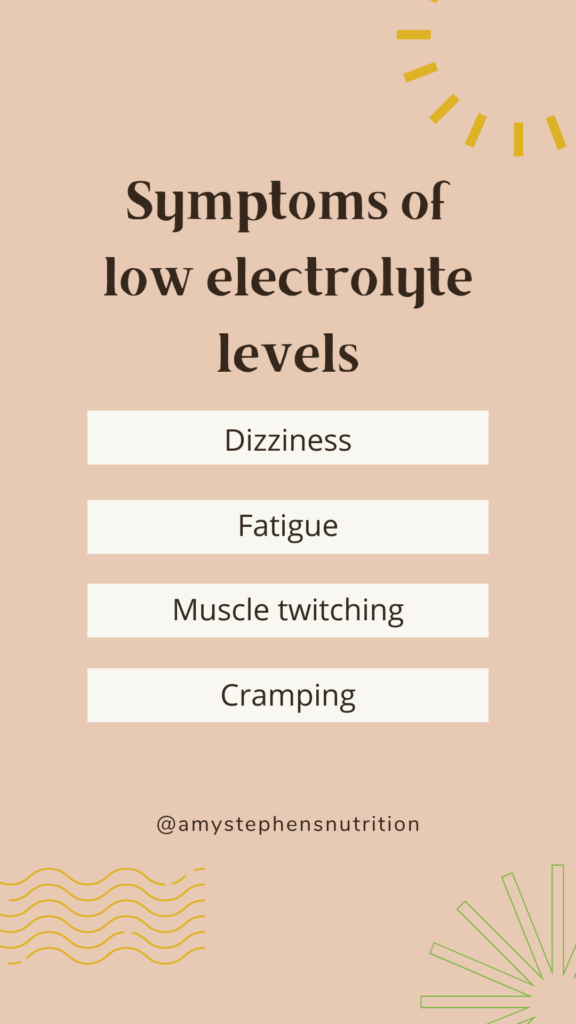

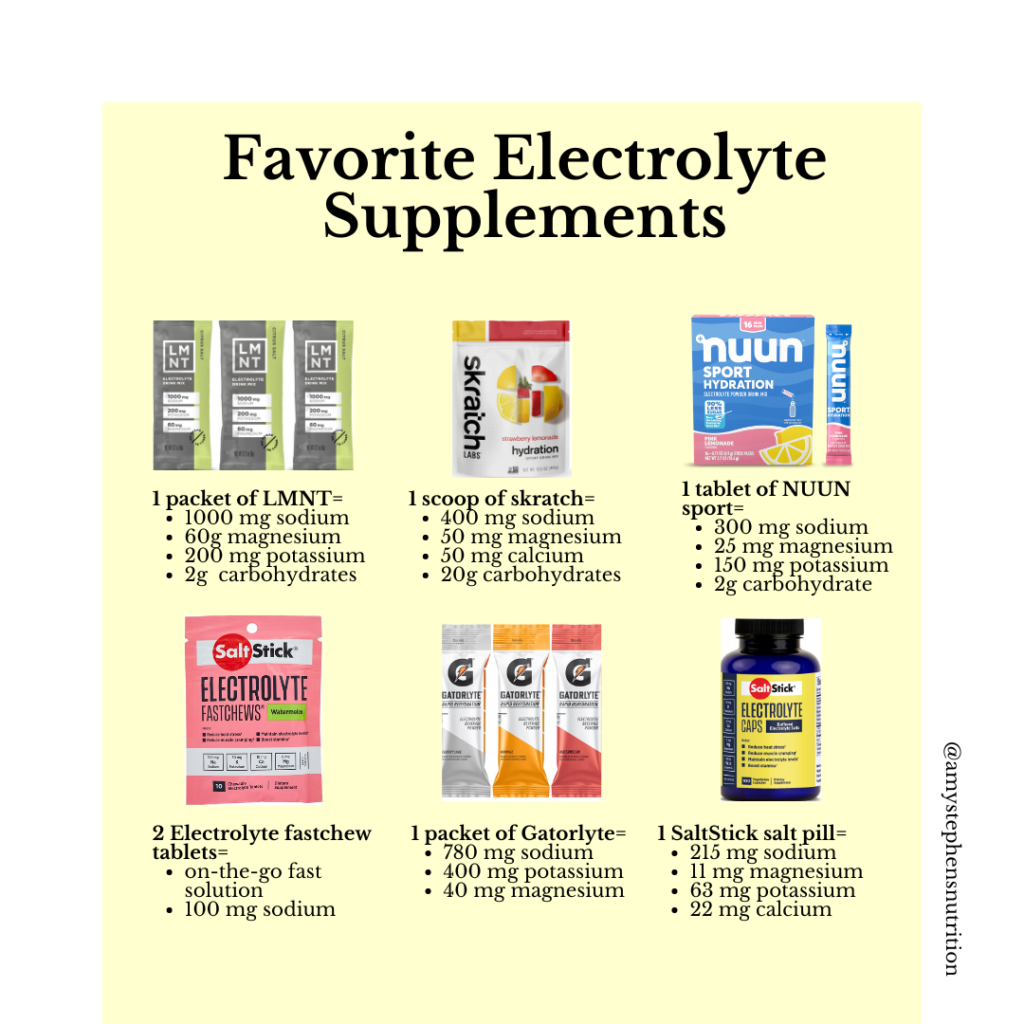

Electrolytes: If the game is intense or in hot weather, consider a sports drink that provides electrolytes to help maintain hydration and replace minerals lost through sweat.

Half-Time Nutrition:

Quick Carbs: Consume easily digestible carbohydrates during half-time to replenish glycogen stores and maintain energy levels. Some examples include:

- Small banana

- Apple slices

- Orange slices

- Apple squeeze packets

- Dried fruit such as mango or raisins

- Energy bar – Clif Zbar

- Pretzels

- Sports drink or coconut water

Foods to avoid at half time: protein bars, fatty foods (chips) or high-fiber foods can cause gastrointestinal issues because they take longer to leave the gut.

Post-Game Recovery:

Hydration: Continue to drink water to replace fluids lost during the game. Replace fluids by sipping water or sports drinks with your post-game meal.

Food: Within an hour of finishing the game, consume a meal or snack that combines carbohydrates and protein to support muscle recovery and glycogen replenishment. Examples include a turkey sandwich, yogurt with fruit, or a protein shake with fruit.

Travel tips:

Frequent travel can make it difficult to keep up with your fueling plan. Pay special attention to timing of meals and snacks to ensure plenty of time for digestion.

- Eat meals 3-4 hours before kick off

- Use insulated coolers to keep beverages cold

- Pack extra snacks

○ Peanut butter and jelly sandwich

○ Trail mix with dried fruit

○ Rice cakes or pita chips and hummus

○ Fresh or dried fruit

○ Granola bar

○ Clif bar

○ Dry cereal

○ Pretzels

○ Peanut butter pretzels

○ Saltines