signs and symptoms of an eating disorder

- By Amy Stephens MS RDN CSSD CEDS and Kate Cochran, Nutrition Intern

TW: This content includes references to eating disorders and body image, which may be a sensitive topic to some readers.

Eating disorders can show up in many different ways, making them difficult to recognize at times. There’s a common belief that you have to fit a specific mold or experience every symptom for an eating disorder to be “real.” This can cause people to downplay their struggles, thinking, “I don’t look a certain way,” or “I’m not xx weight, so it doesn’t count.” But the truth is, eating disorders can affect anyone, regardless of appearance or specific symptoms.

Social media also influences how eating disorders are perceived. While some accounts help raise awareness and normalize conversations, they can also create a narrow picture of what an eating disorder looks like. This might make someone question their own experience if it doesn’t match what they see online—whether in terms of appearance, behaviors, or eating patterns. But the truth is, eating disorders don’t look the same for everyone, and every struggle is valid.

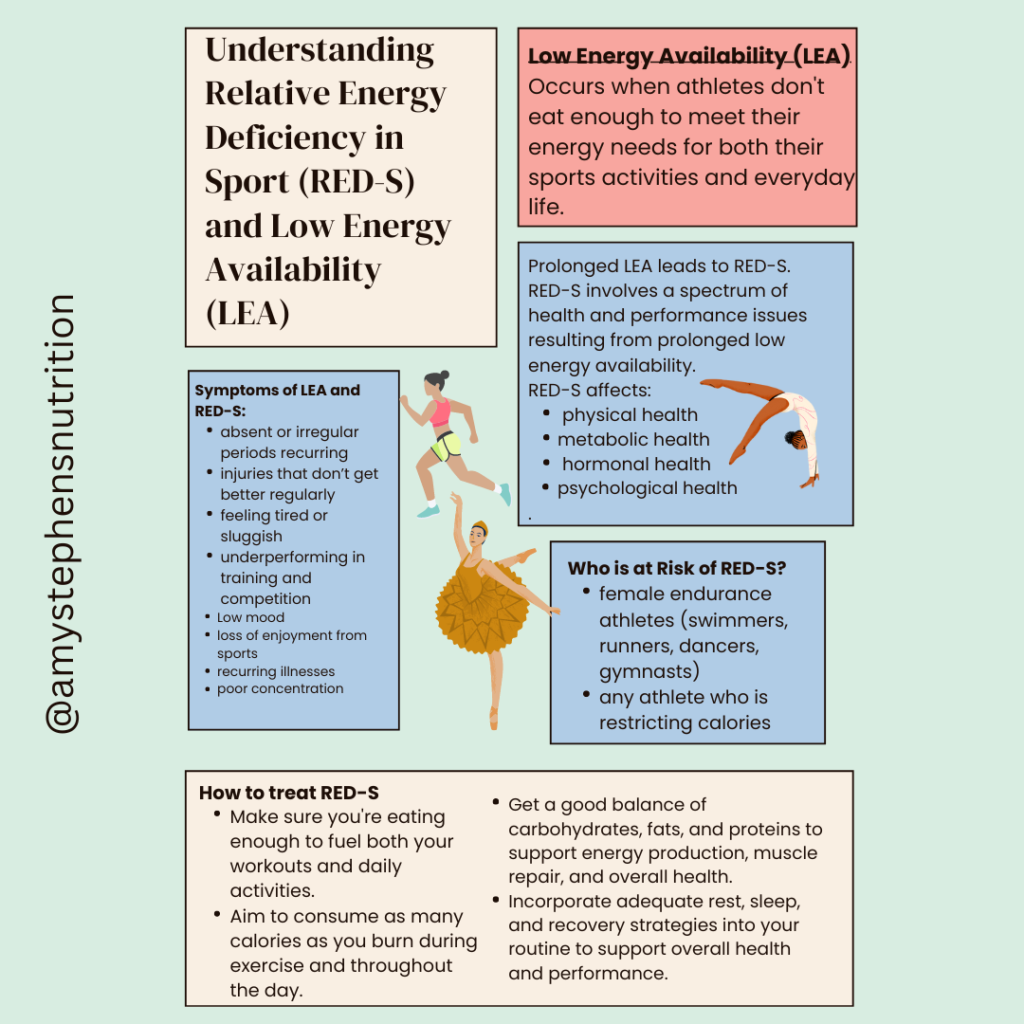

When it comes to sports nutrition, eating disorder symptoms can be a little harder to spot because certain behaviors—like meal planning and intense training—are often seen as part of being an athlete. But there’s a fine line between dedication and disordered habits. Here are some common signs that might indicate an issue:

- Obsession with “clean” eating or only sticking to “healthy” foods.

- Restricting food groups that you once enjoyed.

- Comparing your body to those of your competitors, teammates, or online influencers.

- Skipping meals or eating less than your energy needs require in order to stay light.

- Constantly thinking about food, training, or your body weight/image.

- Avoiding social situations that involve food.

- Viewing training as a way to “burn off” or “earn” food. Food should be seen as fuel for your performance—not something you have to work for or make up for.

Here are some symptoms that results from having an eating disorder or underfueling in general:

- Frequent fatigue, injuries, illnesses, or slow recovery.

- Loss of menstrual cycle (for female athletes).

- Decreased libido (for male athletes).

- Decreased concentration.

- Low heart rate (can often be mistaken for fitness).

- Decreased strength and power.

- Inconsistent energy.

- Dizziness.

- Hypothermia.

- Sleep disturbances or waking up hungry in the middle of the night.

If any of these symptoms resonate with you, there are plenty of ways to assess whether you might need extra support or professional help. One great tool is the Eating Disorders Screen for Athletes (EDSA), which helps gauge the likelihood of an eating disorder—you can check it out here. Another great screening tool is the SCOFF questionnaire.

The SCOFF questions*

Do you make yourself Sick because you feel uncomfortably full?

Do you worry you have lost Control over how much you eat?

Have you recently lost more than One stone in a 3 month period?

Do you believe yourself to be Fat when others say you are too thin?

Would you say that Food dominates your life?

*One point for every “yes”; a score of ≥2 indicates a likely case of anorexia nervosa or bulimia

Keep in mind, you don’t need to experience every symptom for it to be a concern. Even one or two signs are worth paying attention to. Recognizing an eating disorder early is key to getting the right support, as both short-term and long-term effects can impact your health and performance.

If you or someone you know is struggling with an eating disorder, there are several trusted places to turn for help, depending on your needs and location. Talk with your healthcare provider, physician, therapist, or dietitian that specializes in eating disorders. In the US, you can also call or text the National Eating Disorder Association (NEDA) helpline at 1-800-931-2237.

References

Morgan J F, Reid F, Lacey J H. The SCOFF questionnaire: assessment of a new screening tool for eating disorders BMJ 1999; 319 :1467 doi:10.1136/bmj.319.7223.1467.

National Eating Disorders Association. (n.d.). Coaches & trainers: What you need to know. National Eating Disorders Association. https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/coaches-trainers

Eating Disorders Screen for Athletes. (n.d.). EDSA screening tool. https://sites.google.com/view/edsa-screening-tool/

Logue, D. M., Madigan, S. M., Delahunt, E., Heinen, M., Mc Donnell, S. J., Corish, C. A., & Warrington, G. D. (2022). Low energy availability in athletes: A review of prevalence, impact, and assessment. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 32(4), 317–329. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsnem.2022-0033