Amy Stephens

MS, RDN, CSSD, CEDS

Licensed dietitian

specializing in sports nutrition

and eating disorders

MS, RDN, CSSD, CEDS

Licensed dietitian

specializing in sports nutrition

and eating disorders

Why bone health matters

Bone stress injuries (BSI) such as stress fractures and stress reactions are common among athletes with a lifetime prevalence of 40%. They can happen suddenly, just as an athlete might be peaking with training. Most injuries can take about two months to recover. Newer research has identified certain risk factors to help prevent bone stress injuries. Female athletes that miss a period and male athletes that have low testosterone levels are at an increased risk. It’s NOT normal for a female athlete to miss a period. While a missed period is a key indicator that females are at risk of declining bone health, male athletes can also suffer bone stress injuries due to inadequate fueling. Bone injuries are not fully preventable, however there are dietary and lifestyle modifications that can reduce the risk. This blog is intended to educate athletes, parents and coaches about how to optimize bone health. I will explain the relationship of running to bone health and best strategies to optimize bone strength.

How bones are formed

Bones are dynamic tissues. They are breaking down and building up daily.

After a workout, bones are broken down and if adequate nutrients are available, bones will rebuild and remain strong. Rebuilding is dependent on energy availability. This requires eating enough not only to support exercise, but to backfill nutrition requirements for daily living. If there is a lack of nutrition or the energy balance is off, in addition to failing to repair the stress to the bone tissue itself, the muscles will not have enough energy to fire and protect bones, leading to additional damage. This process worsens over time.

Specific cells responsible for breaking down bones (osteoblasts) and building up bones (osteoclast). It’s important for there to be a balance between the two so that bone can maintain its strength. Bones need to be built up at the same rate they are broken down. If muscles are unable to produce adequate force due to under-fueling, the balance is upended. Typically, underfueling prevents bone from being reformed thereby disrupting the breakdown and growth cycle of bones. Disruption to bone formation can occur in as few as five days of underfueling.

Lack of nutrition doesn’t support homeostasis with bones. It doesn’t mean that all exercises cause bone injury; it’s the opposite. Exercise is helpful to strengthen bones because the muscles pull on ligaments and tendons which break bone down. If the body is fueled properly and adequately rested, bones will rebuild stronger. For both male and female athletes, 90% of bone mass peaks by age 20 and will continue, to a lesser extent until 30 years old (Specker).

Underfueling can lead to bone injuries

It’s important for an athlete to consume adequate calories to meet daily nutritional requirements. If the athlete is uable to meet nutritional needs, the energy balance is disrupted.

In a situation of chronic underfueling or inadequate energy balance, the muscles weaken and overuse injuries can develop. In order for the body to work properly, there needs to be a balance with food and activity. Running, in particular, puts excessive strain on bones which has both short-and long-term consequences.

Underfueling for a short time, as little as five days, will increase the risk of a bone stress injury. Bone injuries can come on suddenly, even if you think you’re doing all the right things.

Chronic underfueling has long-term consequences because training suppresses hormones that protect bones (estrogen/testosterone). Over time, gradual bone loss will occur and bones begin to lose density. During adolescent years, achieving maximum bone mass is critical to protect an athlete later in their sports career.

Bone stress injuries can occur at any age. When an athlete is training at an intense level and an inadquate amount of nutrients are consumed, bone stress injuries can develop.

Risk factors for low bone mineral density (BMD)

Low testosterone (male athlete)

Amenorrhea (female athlete)

Inadequate calcium intake

Low Vitamin D levels

Eating disorder (past or present)

Dietary restrictions – vegan, gluten free, lactose free

Inadequate calorie intake

History of stress fracture

Sports at highest risk for bone stress injuries

Swimming

Diving

Crew

Cross country

Dance

Impact of the menstrual cycle on bone health

A normal menstrual cycle lasts approximately 25-35 days, during which estrogen levels increase and decrease, causing menstruation. An abnormal menstrual cycle, either shortened or lengthened between periods, provides a warning sign that requires further evaluation, as it may indicate a hormonal imbalance. Hormonal imbalances such as suppression of estrogen occur if energy balance is not adequate.

Because estrogen plays a significant role in bone formation, fueling adequately to maintain healthy estrogen levels is essential. Low food intake disrupts estrogen production, preventing bones from reaching maximum strength. Changes in bone have been seen in as little as 5 days of underfueling. During phases of amenorrhea (absence of menstruation), bone growth does not occur. Over time, stress from exercise outpaces bone mass maintenance. This imbalance can lead to bone injuries in the short term and bone density issues (osteopenia/osteoporosis) in the future. This is particularly damaging if the athlete wants to continue a post-collegiate athletic career.

If an athlete has irregular periods, speak with a local sports dietitian for further evaluation. If irregular cycles persist, other medical conditions may be the cause. Reach out to your doctor or healthcare center to rule out medical causes of amenorrhea.

Birth control and bone density

Birth control pills have minimal effect on improving bone density. They work by controlling hormones to produce a period. However, the underlying issue of chronic underfueling is not addressed and the hormones are not working naturally to increase bone density. The effect of underfueling prevents the body from making enough hormones.

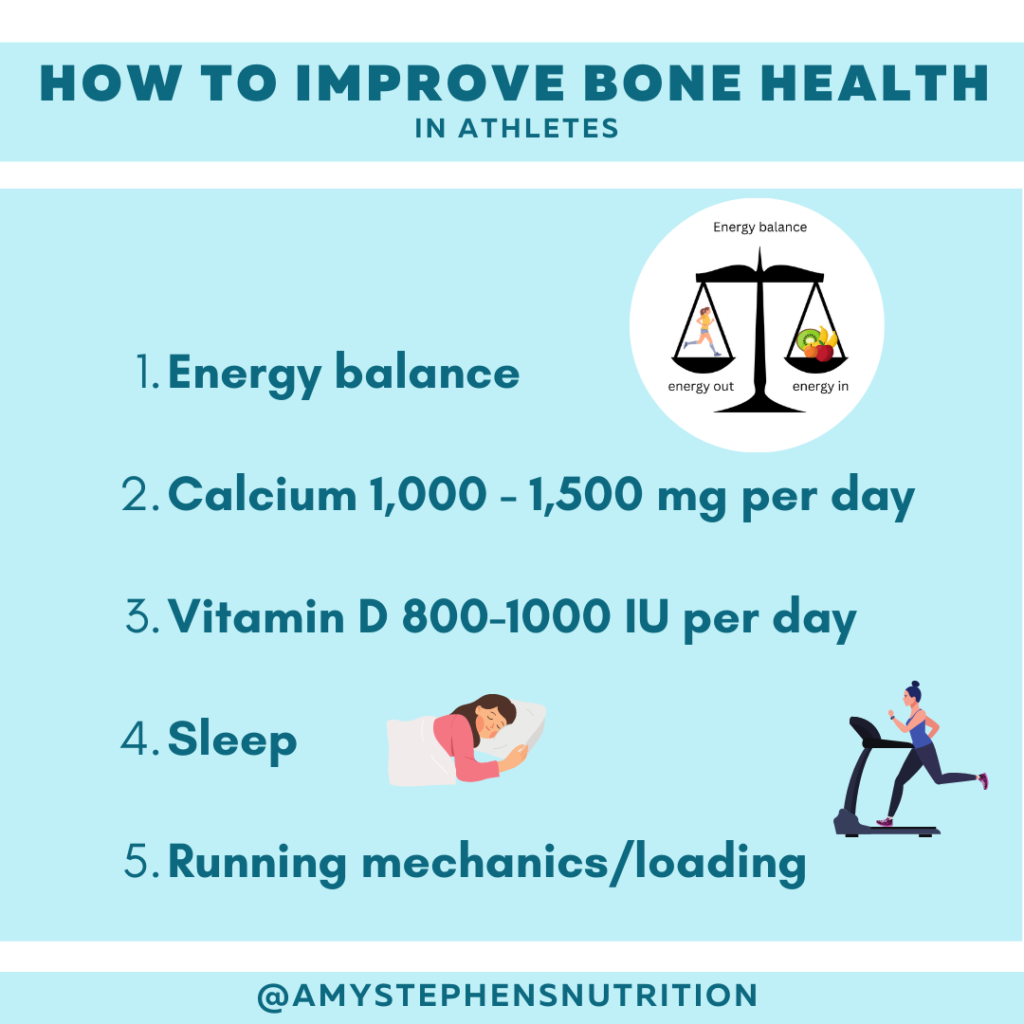

How to improve bone health

Ensure adequate calories/energy balance.

Eat on a schedule. Be proactive. One week of underfueling can drop bone density. Studies have shown that one missed meal can increase bone injury by 40%. Eating on a schedule can help ensure you are eating enough food to support exercise. Plan out meals and snacks to eat before and after workouts. If you know it’s going to be a busy week with travel, bring snacks to fill in gaps between meals. For student athletes, this might require snacking during class or for adult runners to eat during a meeting. The goal is to eat food on a regular basis so the body will function at an optimal level. When exercise exceeds food consumed, the energy available to support bones and other important functions is diminished. The body will prioritize movement and sacrifice bone health.

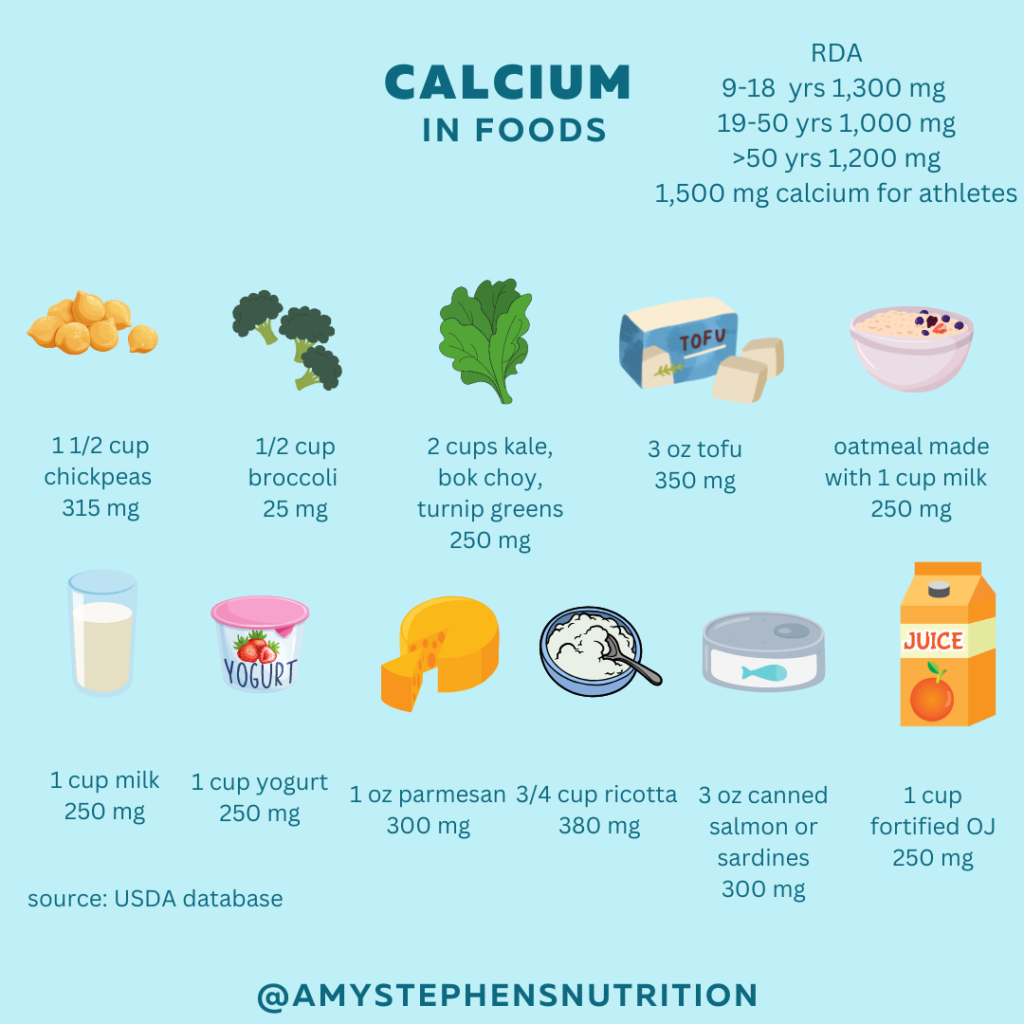

Target the right amount of calcium and vitamin D

Obtain nutrients mainly from foods, and supplement only when necessary to fill in gaps. The RDA for adolescent athletes is 1,300 mg calcium and 600 IU vitamin D. Many foods with calcium also contain adequate amounts of vitamin D. An adolescent athlete can meet calcium requirements with 3 servings of dairy per day. Try eating oatmeal made with milk, yogurt for a snack and adding cheese to sandwiches or as a snack.

Non-dairy athletes can meet calcium requirements by including soymilk, fortified orange juice, dark green leafy vegetables, chickpeas, and fish such as sardines and salmon.

Vitamin D is found in most foods that also have calcium as well as sunlight. Most athletes spend a lot of time outdoors training so supplementation is not always necessary. Sports that are mostly held indoors are at a higher risk of vitamin D deficiency such as swimming, gymnastics, track and field, and dance.

RDA

9-18 yrs old require 1,300 mg calcium and 600 IU Vitamin D

<70 yrs, 1,000 mg of calcium and 600 IU vitamin D

>70 yrs, 1,200 mg of calcium and 800 IU vitamin D

Please note that excessive calcium intake can be harmful and lead to medical issues. Speak with your doctor or healthcare provider about supplementation.

One study by Dr. Nieves showed that one cup of skim milk reduced stress fracture risk by 62%.

“If skim milk were a medicine, it would be a blockbuster.” -Adam Tenforde, MD

Sleep

In addition to high energy demands of athletes, lack of sleep has an even greater risk for bone injury. Impaired sleep has been shown to cause up to 5 percent bone loss within one week (BenSasson 1994).

Exercise loading to build bones

Work with a trained physical therapist to help create a fitness plan that includes a variety of movements. Younger athletes will benefit from a variety of exercises rather than specializing in a single sport. For example, runners will utilize different muscle systems in soccer or basketball. Using multi-directional sports recruits more muscles that strengthen bones from different locations.

If you are worried about your bone density, reach out to a pediatrician, primary care doctor or sports dietitian that works with athletes.

References

Ben-Sasson SA, et al. Extended duration of vertical position might impair bone metabolism. Euro J Clin Investigation. 1994 Jun. Vol 24-6: 421-425. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2362.1994.tb02186.x

Chan JL, Mantzoros CS. Role of leptin in energy-deprivation states: normal human physiology and clinical implications for hypothalamic amenorrhoea and anorexia nervosa. Lancet. 2005 Jul 2-8;366(9479):74-85. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66830-4. PMID: 15993236.

Nieves J, et al. Nutritional Factors That Influence Change in Bone Density and Stress Fracture Risk Among Young Female Cross-Country Runners. PMR Journal. 2010. Aug Vol 2, Issue 8. 740-750. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmrj.2010.04.020

Nieves JW. Bone. Maximizing bone health–magnesium, BMD and fractures. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014 May;10(5):255-6. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2014.39. Epub 2014 Apr 1. PMID: 24686202.

Schoenau E, Frost HM. The “muscle-bone unit” in children and adolescents. Calcif Tissue Int. 2002 May;70(5):405-7. doi: 10.1007/s00223-001-0048-8. Epub 2002 Apr 19. PMID: 11960207.

Specker BL, Wey HE, Smith EP. Rates of bone loss in young adult males. Int J Clin Rheumtol. 2010 Apr 1;5(2):215-228. doi: 10.2217/ijr.10.7. PMID: 20625439; PMCID: PMC2897064.

Swanson CM, Shea SA, Wolfe P, Cain SW, Munch M, Vujovic N, Czeisler CA, Buxton OM, Orwoll ES. Bone Turnover Markers After Sleep Restriction and Circadian Disruption: A Mechanism for Sleep-Related Bone Loss in Humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017 Oct 1;102(10):3722-3730. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-01147. PMID: 28973223; PMCID: PMC5630251.

Tenforde AS, Fredericson M, Sayres LC, Cutti P, Sainani KL. Identifying sex-specific risk factors for low bone mineral density in adolescent runners. Am J Sports Med. 2015 Jun;43(6):1494-504. doi: 10.1177/0363546515572142. Epub 2015 Mar 6. PMID: 25748470.

Tenforde AS, Carlson JL, Sainani KL, Chang AO, Kim JH, Golden NH, Fredericson M. Sport and Triad Risk Factors Influence Bone Mineral Density in Collegiate Athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2018 Dec;50(12):2536-2543. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001711. PMID: 29975299.

Tenforde AS, Barrack MT, Nattiv A, Fredericson M. Parallels with the Female Athlete Triad in Male Athletes. Sports Med. 2016 Feb;46(2):171-82. doi: 10.1007/s40279-015-0411-y. PMID: 26497148.